You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

A New Beginning - Our 1992 Russian Federation

- Thread starter panpiotr

- Start date

-

- Tags

- russia russian federation

Threadmarks

View all 149 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Federal budget Undermining American global financial domination (2010) New game GDP Ranking (2011) Chapter Thirty One: Nothing Lasts Forever (April - December 2010) Part I Chapter Thirty One: Nothing Lasts Forever (April - December 2010) Part II Map of the world (12/2010) Result of the vote (January 2011)1. @Art Vandelay and @Kriss plan1. Please write down how should the Russian government deal with ongoing the Budyonnovsk hostage crisis?

2. Please write down how should the Russian government react to Operation Deliberate Force?

3. Please write down how should the Russian agricultural sector modernized?

2. Russia should not involve in the Yugoslav Wars and declare neutrality.

3. @Kriss plan

I'd personally like to cover French politics when I'll have more timeOk, here is a list of topics covered by you dear readers:

1. Russian Automotive Industry - @Kriss

2. Russian Television - @Screwhorn77

3. Turkey/Turkish politics - @SultanArda

4. Events in the U. S. - @Red Angel

5. TBD - @ruffino

6. TBD - @Empress_Boogalaboo

7. Pro-wrestling - @Dude-a-Buck

Great to hear!I'd personally like to cover French politics when I'll have more time

i woyld like to cover football in russia (like russia on international and club stage)Ok, here is a list of topics covered by you dear readers:

1. Russian Automotive Industry - @Kriss

2. Russian Television - @Screwhorn77

3. Turkey/Turkish politics - @SultanArda

4. Events in the U. S. - @Red Angel

5. TBD - @ruffino

6. TBD - @Empress_Boogalaboo

7. Pro-wrestling - @Dude-a-Buck

8. France - @ArthurS

Last edited:

Great!i woyld like to cover football in russia (like russia on international and club stage)

Football in Russia by 1995

Football in Russia by 1995

History and Current Climate

Notable teams playing in the RSL are Spartak Moscow, Lokomotiv Moscow, CSKA Moscow, Zenit Saint Petersburg, Dynamo Moscow and FC Torpedo Moscow, with the Derby of the East between Spartak Moscow and CSKA Moscow being the most watched and at the same time, heated match in RSL, as there has been many incidents happened with fans of both clubs.

Spartak Moscow, being the biggest and the most supported team in Russia, won all of the championship in the RSL since its beginning in 1992. They've also constantly made the knockout rounds of the Champions League, even make it into the Semi-Finals this year, with them beating the likes of Bayern Munich and Barcelona, before being ultimately beaten by eventual Finalist AC Milan.

National Team

History and Current Climate

With the USSR collapsing in 1991, Russia emerged as its successor state, with the Football Federation of the USSR being transformed into the Russian Football Union (RFU). While the national teams and the clubs used to be linked to state institutions or mass organizations, more of them are starting to became private enterprises, due to limited finance to fund their club.

Citizens of Russia are interested mostly in the national team that gets to compete in the World Cup and the European Championship (Euro), and in the Russian Super League (RSL), where clubs from different cities look to become champions of Russia.

The RSL is rapidly regaining its former strength because of huge sponsorship deals, an influx of finances and a fairly high degree of competitiveness with roughly 7 teams capable of winning the title.

Many notable talented foreign players have been and are playing in the RSL, as well as local talented players worthy of a spot in the starting eleven of the best clubs.

Foreign players sometimes face a very hostile environment, with racism being its main problem, with them being constantly discriminated in matches. RFU has attempted in recent years to put this act of discrimination to an end, but to no avail.

Corruption is also an big stepping stones of Russian football. Local talents from local teams are often snatched away from big club owned by oligarchs or consortium and being paid loads of money, resulting in them starting to stop training and to sink in luxurious lifestyle.

Football right now, are considered by the masses, as the 'riches games' due to the difficulties to be a footballer, its youth development being close to zero, and with oligarchs preferring profits by buying clubs outside of Russia. Fortunately, the RFU has been trying to combat this situation by reforming through its initiatives, such as:

Citizens of Russia are interested mostly in the national team that gets to compete in the World Cup and the European Championship (Euro), and in the Russian Super League (RSL), where clubs from different cities look to become champions of Russia.

The RSL is rapidly regaining its former strength because of huge sponsorship deals, an influx of finances and a fairly high degree of competitiveness with roughly 7 teams capable of winning the title.

Many notable talented foreign players have been and are playing in the RSL, as well as local talented players worthy of a spot in the starting eleven of the best clubs.

Foreign players sometimes face a very hostile environment, with racism being its main problem, with them being constantly discriminated in matches. RFU has attempted in recent years to put this act of discrimination to an end, but to no avail.

Corruption is also an big stepping stones of Russian football. Local talents from local teams are often snatched away from big club owned by oligarchs or consortium and being paid loads of money, resulting in them starting to stop training and to sink in luxurious lifestyle.

Football right now, are considered by the masses, as the 'riches games' due to the difficulties to be a footballer, its youth development being close to zero, and with oligarchs preferring profits by buying clubs outside of Russia. Fortunately, the RFU has been trying to combat this situation by reforming through its initiatives, such as:

- establishing football clubs in schools

- improving and building football infrastructures (football fields, etc)

- establishing an youth academy system and improving its training system

- making football more affordable by pushing its fees down

- zero-tolerance action against corruption and cheating (such as match-fixing and doping)

- establishing football coaching schools to develop UEFA-level football coaches

- establishing referee school to prevent unfair or bias decisions by a referee

- increasing football publicity to let more people to be able to participate in football

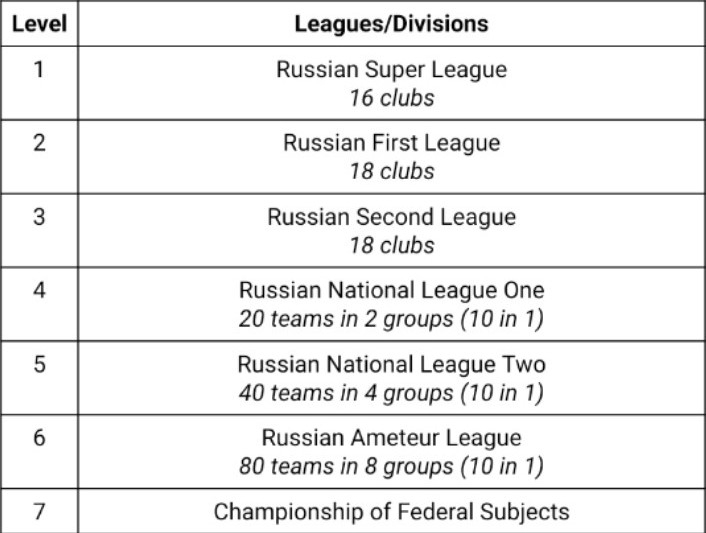

Currently, the Russian football pyramid has 7 leagues and divisions under it, with its flagship being the RSL, with the Russian Cup and the Russian Super Cup being its cup completion.

Football League Structure in Russia

Notable teams playing in the RSL are Spartak Moscow, Lokomotiv Moscow, CSKA Moscow, Zenit Saint Petersburg, Dynamo Moscow and FC Torpedo Moscow, with the Derby of the East between Spartak Moscow and CSKA Moscow being the most watched and at the same time, heated match in RSL, as there has been many incidents happened with fans of both clubs.

Spartak Moscow, being the biggest and the most supported team in Russia, won all of the championship in the RSL since its beginning in 1992. They've also constantly made the knockout rounds of the Champions League, even make it into the Semi-Finals this year, with them beating the likes of Bayern Munich and Barcelona, before being ultimately beaten by eventual Finalist AC Milan.

National Team

After the dissolution of Soviet Union (and consequently the Soviet Union National Team), Russia started big with them qualifying in Euro 1992 held in Sweden, in which they made it to the Semi-Finals, before being beaten by eventual Finalist Sweden. They would qualify for World Cup 1994 held in the United States, in which they are unable to make it out of the group stage. The only good news coming from the tournament is that Oleg Salenko became the joint top scorer along with Hristo Stoichkov (who eventually won the Golden Boot).

Oleg Romantsev currently leads the Russian National Team, who is currently also the manager of Spartak Moscow. Viktor Onopko from Spartak Moscow currently captains Russia.

Russia are known for their discipline, and fierce rules and fines whenever their player breaks one, as introduced by Romantsev. As a result, there has been many fuss from their player, but in the end work out.

They are currently ranked 17th place in FIFA Men's Ranking, and are currently trying to become a major Football force in the world, and to catch up with the soviet-era force.

Oleg Romantsev currently leads the Russian National Team, who is currently also the manager of Spartak Moscow. Viktor Onopko from Spartak Moscow currently captains Russia.

Russia are known for their discipline, and fierce rules and fines whenever their player breaks one, as introduced by Romantsev. As a result, there has been many fuss from their player, but in the end work out.

They are currently ranked 17th place in FIFA Men's Ranking, and are currently trying to become a major Football force in the world, and to catch up with the soviet-era force.

Last edited:

Thanks for the post!Football in Russia by 1995

History

With the USSR collapsing in 1991, Russia emerged as its successor state, with the Football Federation of the USSR being transformed into the Russian Football Union. While the national teams and the clubs used to be linked to state institutions or mass organizations, more of them are starting to became private enterprises, due to limited finance to fund their club.

Citizens of Russia are interested mostly in the national team that gets to compete in the World Cup and the European Championship, and in the Russian Super League (RSL), where clubs from different cities look to become champions of Russia.

Many notable talented foreign players have been and are playing in the RSL, as well as local talented players worthy of a spot in the starting eleven of the best clubs. Foreign players sometimes face a very hostile environment. A problem of racism in Russian football is particularly important.

League Structure and Spartak

Currently, the Russian football pyramid has 7 leagues and divisions under it, with its flagship being the RSL, with the Russian Cup and the Russian Super Cup being its cup completion.

View attachment 875995Football League Structure in Russia

Notable teams playing in the RSL are Spartak Moscow, Lokomotiv Moscow, CSKA Moscow, Zenit Saint Petersburg, Dynamo Moscow and FC Torpedo Moscow, with the Derby of the East between Spartak Moscow and CSKA Moscow being tge most watched match in RSL.

Spartak Moscow, being the biggest and the most supported team in Russia, won all of the championship in the RSL since its beginning in 1992. They've also constantly reach the knockout rounds of the Champions League, even make it into the Semi-Finals this year, with them beating the likes of Bayern Munich and Barcelona, before being ultimately beaten by eventual Finalist AC Milan.

National Team

After the dissolution of Soviet Union (and consequently the Soviet Union National Team), Russia started big with them qualifying in the European Championship (Euro) held in Sweden in 1992, in which they made it to the Semi-Finals, before being beaten by eventual Finalist Sweden. They would qualify for World Cup held in the United States in 1994, in which they are unable to make it out of the group stage.

Oleg Romantsev currently leads the Russian National Team, who is currently also the manager of Spartak Moscow. Viktor Onopko from Spartak Moscow currently captains Russia.

They are currently ranked 17th place in FIFA Men's Ranking, and are currently trying to being a major Football power in the world.

Who won euro 1992 and world cup in 1994?Football in Russia by 1995

History

With the USSR collapsing in 1991, Russia emerged as its successor state, with the Football Federation of the USSR being transformed into the Russian Football Union (RFU). While the national teams and the clubs used to be linked to state institutions or mass organizations, more of them are starting to became private enterprises, due to limited finance to fund their club.

Citizens of Russia are interested mostly in the national team that gets to compete in the World Cup and the European Championship (Euro), and in the Russian Super League (RSL), where clubs from different cities look to become champions of Russia.

The RSL is rapidly regaining its former strength because of huge sponsorship deals, an influx of finances and a fairly high degree of competitiveness with roughly 7 teams capable of winning the title.

Many notable talented foreign players have been and are playing in the RSL, as well as local talented players worthy of a spot in the starting eleven of the best clubs.

Foreign players sometimes face a very hostile environment, with racism being its main problem, with them being constantly discriminated in matches. RFU has attempted in recent years to put this act of discrimination to an end, but to no avail.

League Structure and Spartak

Currently, the Russian football pyramid has 7 leagues and divisions under it, with its flagship being the RSL, with the Russian Cup and the Russian Super Cup being its cup completion.

View attachment 875995Football League Structure in Russia

Notable teams playing in the RSL are Spartak Moscow, Lokomotiv Moscow, CSKA Moscow, Zenit Saint Petersburg, Dynamo Moscow and FC Torpedo Moscow, with the Derby of the East between Spartak Moscow and CSKA Moscow being the most watched and at the same time, heated match in RSL, as there has been many accident happened with fans of both clubs.

Spartak Moscow, being the biggest and the most supported team in Russia, won all of the championship in the RSL since its beginning in 1992. They've also constantly reach the knockout rounds of the Champions League, even make it into the Semi-Finals this year, with them beating the likes of Bayern Munich and Barcelona, before being ultimately beaten by eventual Finalist AC Milan.

National Team

After the dissolution of Soviet Union (and consequently the Soviet Union National Team), Russia started big with them qualifying in Euro 1992 held in Sweden, in which they made it to the Semi-Finals, before being beaten by eventual Finalist Sweden. They would qualify for World Cup 1994 held in the United States, in which they are unable to make it out of the group stage.

Oleg Romantsev currently leads the Russian National Team, who is currently also the manager of Spartak Moscow. Viktor Onopko from Spartak Moscow currently captains Russia.

They are currently ranked 17th place in FIFA Men's Ranking, and are currently trying to become a major Football force in the world, with the Fyodorov government investing heavily into the Football Industry and infrastructure in Russia. They are currently planning to host the World Cup and the Euro in the near future.

Last edited:

denmark in 1992 and italy in 1994Who won euro 1992 and world cup in 1994?

Politics in Spain in 1990s

Politics in Spain in 1990

The 90s begin in Spain with the reaffirmation of the absolute majority victory of Felipe Gonzalez, leader of the PSOE (Spanish Socialist Workers' Party), with leftist ideology.

Gonzalez has been governing Spain since 1982, being the first president of a left-wing party and the third president of Spain since democracy returned in 1978.

The period from 1982 to 1990 was a great success for Gonzalez, who achieved accession to the European Economic Community in 1985 and the victory to remain in NATO in the 1986 referendum, although he was famous at the time in the opposition rejection of it: "OTAN de entrada no" (not with the NATO ).

Although it is not without setbacks. Like the Rumasa Case in 1983, which was the expropriation of the Rumasa holding company from businessman Ruiz Mateos with the justification of opacity of accounts and risk of bankruptcy. This expropriation would be very controversial with numerous detractors and defenders of it, and the General Strike of 1988 called by the main unions, including UGT (General Union of Workers), historically linked to the PSOE, on the occasion of the labor reform approved by the PSOE, by which, among other measures,

Dismissals were made cheaper and temporary employment contracts were introduced for workers.

(signing of the Spanish accession to the EEC)

(general strike of 1988)

1990, on the surface, should start well for the Spanish Government, with absolute victory in the 1989 elections, the Universal Exposition of Seville and the Barcelona Olympic Games in 1992, but soon the dark things began, among them, a corruption scandal that affects the Vice President of the Government, Alfonso Guerra, who is accused to benefit his family, in particular his brother, and forces the Vice President to resign.

(newspaper headlines of the time about the Guerra Case, the one on the left says "González is summoned to clarify Guerra's brother's business" and the one on the right says "Industry illegally favors a company represented by Juan Guerra")

From here on, things only get worse for President Gonzalez, who although he won again in 1993, did so in a position of simple majority, forced to make agreements with other parties. 1993 and 1994 were terrible years, with the outbreak of the Roldán Case (corruption and escape of the General Director of the Civil Guard) and the confirmation of the GAL (Anti-Terrorist Liberation Groups), which were parapolice groups that fought against the organization's terrorism. ETA, operating in Spanish and French territory, murdering both members of the terrorist group and innocent people.

(symbol of the GAL, as opposed to that of the terrorist group ETA, which was a snake around an axe, in that of the GAL, the ax decapitates the snake)

The 90s begin in Spain with the reaffirmation of the absolute majority victory of Felipe Gonzalez, leader of the PSOE (Spanish Socialist Workers' Party), with leftist ideology.

Gonzalez has been governing Spain since 1982, being the first president of a left-wing party and the third president of Spain since democracy returned in 1978.

The period from 1982 to 1990 was a great success for Gonzalez, who achieved accession to the European Economic Community in 1985 and the victory to remain in NATO in the 1986 referendum, although he was famous at the time in the opposition rejection of it: "OTAN de entrada no" (not with the NATO ).

Although it is not without setbacks. Like the Rumasa Case in 1983, which was the expropriation of the Rumasa holding company from businessman Ruiz Mateos with the justification of opacity of accounts and risk of bankruptcy. This expropriation would be very controversial with numerous detractors and defenders of it, and the General Strike of 1988 called by the main unions, including UGT (General Union of Workers), historically linked to the PSOE, on the occasion of the labor reform approved by the PSOE, by which, among other measures,

Dismissals were made cheaper and temporary employment contracts were introduced for workers.

(signing of the Spanish accession to the EEC)

(general strike of 1988)

1990, on the surface, should start well for the Spanish Government, with absolute victory in the 1989 elections, the Universal Exposition of Seville and the Barcelona Olympic Games in 1992, but soon the dark things began, among them, a corruption scandal that affects the Vice President of the Government, Alfonso Guerra, who is accused to benefit his family, in particular his brother, and forces the Vice President to resign.

(newspaper headlines of the time about the Guerra Case, the one on the left says "González is summoned to clarify Guerra's brother's business" and the one on the right says "Industry illegally favors a company represented by Juan Guerra")

From here on, things only get worse for President Gonzalez, who although he won again in 1993, did so in a position of simple majority, forced to make agreements with other parties. 1993 and 1994 were terrible years, with the outbreak of the Roldán Case (corruption and escape of the General Director of the Civil Guard) and the confirmation of the GAL (Anti-Terrorist Liberation Groups), which were parapolice groups that fought against the organization's terrorism. ETA, operating in Spanish and French territory, murdering both members of the terrorist group and innocent people.

(symbol of the GAL, as opposed to that of the terrorist group ETA, which was a snake around an axe, in that of the GAL, the ax decapitates the snake)

We can have a vote on that.Some fun ideas: Can we rename Kaliningrad to Nevskygrad?

Please write down how should the Russian government deal with ongoing the Budyonnovsk hostage crisis?

2. Please write down how should the Russian government react to Operation Deliberate Force?

You know, while the hostage crises might be awful, in a way it came at a opportune time given the nature of Jihadist networking allowing you to link polices together .

By that Shamil Basayev has the 'honour'' of actually going to Afghanistan and meeting up with AQ and for a while was suspected of meeting Bin Laden and think he did lie about doing so.

AQ is also fighting in Bosnia and so it might be possible to tie in domestic and international affairs to each other and explain Russia's actions.

It also is true to a degree.

You know, while the hostage crises might be awful, in a way it came at a opportune time given the nature of Jihadist networking allowing you to link polices together .

By that Shamil Basayev has the 'honour'' of actually going to Afghanistan and meeting up with AQ and for a while was suspected of meeting Bin Laden and think he did lie about doing so.

AQ is also fighting in Bosnia and so it might be possible to tie in domestic and international affairs to each other and explain Russia's actions.

It also is true to a degree.

I agree here, we should definitely tie Jihadist movement to Bosnia to justify our actions.

Chapter Eleven: Foundations of Geopolitics and the Siege of Kizlyar (October 1995 - April 1996)

(Russian troops during the Budyonnovsk hostage crisis)

The Russian government rejected demands from the Chechen jihadists; nevertheless, for three days, negotiations with the terrorists were conducted in order to ensure the safety of the hostages. Unfortunately, on the third day of the hostage crisis, the terrorists killed five hostages when the reporters did not arrive at the hospital. The New York Times quoted the hospital's chief doctor as saying that "several of the Chechens had just grabbed five hostages at random and shot them to show the world they were serious in their demands that Russian troops leave their land. After this, President Fyodorov ordered the security forces to retake the hospital compound. The forces employed were MVD police ("militsiya") and Internal Troops, along with spetsnaz (special forces) from the Federal Security Service (FSB), including the elite Alpha Group. The strike force attacked the hospital compound at dawn on the fourth day, meeting fierce resistance. After several hours of fighting in which many hostages were killed by crossfire, a local ceasefire was agreed on and 227 hostages were released; 61 others were freed by the Russian troops. A second Russian attack on the hospital a few hours later also failed. The third and final attack by the Russian troops succeeded in retaking the hospital compound and killing all the terrorists, although the Chechens were using hostages as human shields, which resulted in around 300 hostages being killed. The terrorist attack was condemned by the international community; nevertheless, the raid scared the Russian public of the possibility of other terrorist attacks in Russia in the future, which turned out to be true later.

Operation Deliberate Force was strongly condemned by the Russian government as an unlawful and unjustified action by the United States and NATO. The West was informed that Russia would no longer stay idle and observe the Western attacks against the Serbs. Furthermore, the Russian government threatened the West with official diplomatic recognition of the Republika Srpska if further attacks against Serbian forces in Bosnia occurred. While the negotiations between Russia and the West over the future of Bosnia were underway, Russia sent numerous pieces of equipment and volunteers to Serbia. Finally, the Dayton Agreement was signed, which was a peace agreement that was reached at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base near Dayton, Ohio, United States, finalised on 21 November 1995, and formally signed in Paris, on 14 December 1995. These accords put an end to the three-and-a-half-year-long Bosnian War, which was part of the much larger Yugoslav Wars. The warring parties agreed to peace and to a single neutral state known as Confederation of Bosnia and Herzegovina composed of two parts, the largely Serb-populated Republika Srpska and the mainly Croat-Bosniak-populated Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

(Thanks to the reform, Russian agricultural sector would boost output in the coming decades)

In the meantime, the reform of the agricultural sector was introduced in Russia and comprised the following points:

- establishment of a Federal Agricultural Fund tasked with subsidizing and modernizing the agricultural sector in Russia;

- development and expansion of domestic fertilizers' production capabilities;

- increased mechanization;

- more funds dedicated to agricultural education;

- expansion and modernization of greenhouses across Russia;

- increased state investments in the cattle industry.

(Cover of the Russian edition of Foundations of Geopolitics)

The Foundations of Geopolitics: The Geopolitical Future of Russia published by a far-right philosopher Aleksand Dugin, was the one most important publications in Russia in the 1990s, as Dugin's publication had a significant influence within the Russian military, police, and foreign policy elites, and and has been used as a textbook in the Academy of the General Staff of the Russian military. Powerful Russian political figures subsequently took an interest in Dugin, a Russian political analyst who espouses an ultranationalist and neo-fascist ideology based on his idea of neo-Eurasianism, who has developed a close relationship with Russia's Academy of the General Staff.

Dugin was born in Moscow, into the family of a colonel-general in the GRU, a Soviet military intelligence agency, and candidate of law, Geliy Aleksandrovich Dugin, and his wife Galina, a doctor and candidate of medicine. His father left the family when he was three, but ensured that they had a good standard of living, and helped Dugin out of trouble with the authorities on occasion. He was transferred to the customs service due to his son's behaviour in 1983. In 1979, Aleksandr entered the Moscow Aviation Institute. He was expelled without a degree either because of low academic achievement, dissident activities or both. Afterwards, he began working as a street cleaner. He used a forged reader's card to access the Lenin Library and continue studying. However, other sources claim he instead started working in a KGB archive, where he had access to banned literature on Masonry, fascism, and paganism. In 1980, Dugin joined the "Yuzhinsky circle", an avant-garde dissident group which dabbled in Satanism, esoteric Nazism and other forms of the occult. In the group, he was known for his embrace of Nazism which he attributes to a rebellion against his Soviet raising, as opposed to genuine sympathy for Hitler. He adopted an alter ego with the name of "ans Sievers", a reference to Wolfram Sievers, a Nazi researcher of the paranormal. Studying by himself, he learned to speak Italian, German, French, English, and Spanish. He was influenced by René Guénon and by the Traditionalist School. In the Lenin Library, he discovered the writings of Julius Evola, whose book Pagan Imperialism he translated into Russian.

In the 1980s, Dugin was a dissident and an anti-communist. Dugin worked as a journalist before becoming involved in politics just before the fall of communism. In 1988, he and his friend Geydar Dzhemal joined the ultranationalist and antisemitic group Pamyat (Memory), which would later give rise to Russian fascism. For a brief period at the beginning of the 1990s he was close to Gennady Zyuganov, leader of the newly formed Communist Party of the Russian Federation, and probably had a role in formulating its nationalist communist ideology. In 1993 he co-founded, together with Eduard Limonov, the National Bolshevik Party, whose nationalistic interpretation of Bolshevism was based on the ideas of Ernst Niekisch. Dugin published Foundations of Geopolitics in 1996. The book was published in multiple editions, and is used in university courses on geopolitics, reportedly including the Academy of the General Staff of the Russian military. It alarmed political scientists in the US, and is sometimes referenced by them as being "Russia's Manifest Destiny". Dugin credited General Nikolai Klokotov of the Academy of the General Staff as co-author and his main inspiration, though Klokotov denies this. Colonel General Leonid Ivashov, head of the International Department of the Russian Ministry of Defence, helped draft the book. Klokotov stated that in the future the book would "serve as a mighty ideological foundation for preparing a new military command". Dugin has asserted that the book has been adopted as a textbook in many Russian educational institutions. Gennadiy Seleznyov, for whom Dugin was adviser on geopolitics,"urged that Dugin's geopolitical doctrine be made a compulsory part of the school curriculum".

(Dugin as an far-right political philosopher would play a very important role in the coming decades in Russia)

Dugin's publication brought the renaissance of Eurasianism, which was socio-political movement in Russia that emerged in the early 20th century which states that Russia does not belong in the "European" or "Asian" categories but instead to the geopolitical concept of Eurasia governed by the "Russian world" forming an ostensibly standalone Russian civilization. The roots of Eurasianism lie in Russia’s Bolshevik Revolution, although many of the ideas that it contains have much longer histories in Russia. After the 1917 October Revolution and the civil war that followed, two million anti-Bolshevik Russians fled the country. From Sofia to Berlin and then Paris, some of these exiled Russian intellectuals worked to create an alternative to the Bolshevik project. One of those alternatives eventually became the Eurasianist ideology. Proponents of this idea posited that Russia’s Westernizers and Bolsheviks were both wrong: Westernizers for believing that Russia was a (lagging) part of European civilization and calling for democratic development; Bolsheviks for presuming that the whole country needed restructuring through class confrontation and a global revolution of the working class. Rather, Eurasianists stressed, Russia was a unique civilization with its own path and historical mission: To create a different center of power and culture that would be neither European nor Asian but have traits of both. Eurasianists believed in the eventual downfall of the West and that it was Russia’s time to be the world’s prime exemplar.

In 1921, the exiled thinkers Georges Florovsky, Nikolai Trubetzkoy, Petr Savitskii, and Petr Suvchinsky published a collection of articles titled Exodus to the East, which marked the official birth of the Eurasianist ideology. The book was centered on the idea that Russia’s geography is its fate and that there is nothing any ruler can do to unbind himself from the necessities of securing his lands. Given Russia’s vastness, they believed, its leaders must think imperially, consuming and assimilating dangerous populations on every border. Meanwhile, they regarded any form of democracy, open economy, local governance, or secular freedom as highly dangerous and unacceptable. In that sense, Eurasianists considered Peter the Great - who tried to Europeanize Russia in the eighteenth century - an enemy and a traitor. Instead, they looked with favor on Tatar-Mongol rule, between the thirteenth and fifteenth centuries, when Genghis Khan’s empire had taught Russians crucial lessons about building a strong, centralized state and pyramid-like system of submission and control.

Eurasianist beliefs gained a strong following within the politically active part of the emigrant community, or White Russians, who were eager to promote any alternative to Bolshevism. However, the philosophy was utterly ignored, and even suppressed in the Soviet Union, and it practically died with its creators. That is, until the 1990s, when the Soviet Union collapsed and Russia’s ideological slate was wiped clean. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, ultranationalist ideologies were decidedly out of vogue. Rather, most Russians looked forward to Russia’s democratization and reintegration with the world. Still, a few hard-core patriotic elements remained that opposed de-Sovietization and believed - that the collapse of the Soviet Union was the greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the century. Among them was the ideologist Alexander Dugin, who was a regular contributor to the ultranationalist analytic center and newspaper Den’ (later known as Zavtra). His earliest claim to fame was a 1991 pamphlet, “The War of the Continents,” in which he described an ongoing geopolitical struggle between the two types of global powers: land powers, or “Eternal Rome,” which are based on the principles of statehood, communality, idealism, and the superiority of the common good, and civilizations of the sea, or “Eternal Carthage,” which are based on individualism, trade, and materialism. In Dugin’s understanding, “Eternal Carthage,” was historically embodied by Athenian democracy and the Dutch and British Empires. Now, it is represented by the United States. “Eternal Rome” is embodied by Russia. For Dugin, the conflict between the two will last until one is destroyed completely - no type of political regime and no amount of trade can stop that. In order for the “good” (Russia) to eventually defeat the “bad” (United States), he wrote, a conservative revolution must take place.

Dugin's ideas of conservative revolution were adapted from German interwar thinkers who promoted the destruction of the individualistic liberal order and the commercial culture of industrial and urban civilization in favor of a new order based on conservative values such as the submission of individual needs and desires to the needs of the many, a state-organized economy, and traditional values for society based on a quasi-religious view of the world. For Dugin, the prime example of a conservative revolution was the radical, Nazi-sponsored north Italian Social Republic of Salò (1943–45). Indeed, Dugin continuously returned to what he saw as the virtues of Nazi practices and voiced appreciation for the SS and Herman Wirth’s occult Ahnenerbe group. In particular, Dugin praised the orthodox conservative-revolutionary projects that the SS and Ahnenerbe developed for postwar Europe, in which they envisioned a new, unified Europe regulated by a feudal system of ethnically separated regions that would serve as vassals to the German suzerain. It is worth noting that, among other projects, the Ahnenerbe was responsible for all the experiments on humans in the Auschwitz and Dachau concentration camps.

In Foundations of Geopolitics, Dugin made a distinction between "Atlantic" and "Eurasian" societies, which means, as Benjamin R. Teitelbaum describes it "between societies whose coastal geographical position made them cosmopolitan and landlocked societies oriented toward preservation and cohesion". Dugin calls for the "Atlantic societies", primarily represented by the United States, to lose their broader geopolitical influence in Eurasia, and for Russia to rebuild its influence through annexations and alliances. The book declares that "the battle for the world rule of Russians" has not ended and Russia remains "the staging area of a new anti-bourgeois, anti-American revolution". The Eurasian Empire will be constructed "on the fundamental principle of the common enemy: the rejection of Atlanticism, strategic control of the U.S., and the refusal to allow liberal values to dominate us."Interestingly, it seems he does not rule out the possibility of Russia joining and/or even supporting EU and NATO instrumentally in a pragmatic way of further Western subversion against geopolitical "Americanism". Military operations play a relatively minor role except for the military intelligence operations he calls "special military operations". The textbook advocates a sophisticated program of subversion, destabilization, and disinformation spearheaded by the Russian special services. The operations should be assisted by a tough, hard-headed utilization of Russia's gas, oil, and natural resources to bully and pressure other countries. The book states that "the maximum task [of the future] is the 'Finlandization' of all of Europe". Following success of his publication, Dugin began working as official adviser to new Minister of Foreign Affairs Igor Ivanov and Deputy Prime Minister Anatoly Sobchak. Furthermore, Dugin became the head of the Department of Sociology of International Relations at Moscow State University.

(The Siege of Kizlyar resulted in 900 hostage deaths)

The Kizlyar hostage crisis, also known in Russia as the terrorist act in Kizlyar, occurred in January 1996. What began as a raid by Chechen jihadists forces led by Salman Raduyev against a federal military airbase near Kizlyar, Dagestan, became a hostage crisis involving thousands of civilians. It culminated in a battle between the Chechens and Russian special forces in the city of Kizlyar, which was destroyed by Russian artillery fire. During the battle, at least 960 hostages and more than 350 combatants on both sides died. On January 9, 1996, a force of about 200 Chechen jihadists led by Salman Raduyev, calling themselves Lone Wolf launched a raid similar to the one triggering the Budyonnovsk hospital hostage crisis. The city of Kizlyar in the neighbouring republic of Dagestan, the site of the first Imperial Russian fort in the region (and many historical battles), was chosen as the target due to its proximity and easy access of 3 kilometres (2 mi) from the Chechen border across flat terrain. The guerrillas began the raid with a nighttime assault on a military airbase outside Kizlyar, where they destroyed at least two helicopters and killed 33 servicemen, before withdrawing.

At 6 am, pursued by Russian reinforcements, the withdrawing Chechen terrorists entered the town itself and took hostage an estimated 2,000 to 3,400 people (according to official Russian accounts, there were "no more than 1,200" hostages taken). The hostages were rounded up in multiple locations and taken to the occupied city hospital and a nearby high-rise building. Field commander Khunkar-Pasha Israpilov later said that he took command of the operation from Raduyev after the latter failed in his mission to destroy the airbase, an ammunition factory and other military and police installations in and around the city. At least 46 people died on January 9. Although on January 12 the rebels freed the women and children, they said they would release the male hostages only if four Russian officials took their places. The Chechens installed most of the hostages in the city school and the mosque and set up defensive positions, putting the captured policemen and some civilian hostages to work digging trenches. Over the next three days Russian special-forces detachments from a number of services, numbering about 500 and supported by tanks, armored vehicles and attack helicopters, repeatedly tried to penetrate the city but they were beaten back with heavy losses, including at least 12 killed. Among the dead was the commander of Moscow special police force SOBR, Andrei Krestyaninov; surviving commandos described the fighting as "hell".

(Chechen jihadist with bodies of Russian troops during the Siege of Kizlyar)

After the assault attempts failed, Russian commanders then ordered their forces to open fire on the city with mortars, howitzers and rocket launchers. American correspondent Michael Specter reported that the Russians were "firing into Kizlyar at the rate of one a minute – the same Grad missiles they used to largely destroy the Chechen capital Grozny when the conflict began." Specter noted: "The Grads fell with monstrous concussive force throughout the day. In this town, about 6 kilometres (4 mi) away, where journalists have been herded by Russian forces, windows cracked at the force of the repeated blasts ... Mikhailov said today that he was adding up the Chechen casualties, not by number of corpses, 'but by the number of arms and legs.'"[Barsukov later joked that "the usage of the Grad multiple rocket launchers was mainly psychological", and CNN reported that "the general's answers were openly mocking." Among Russian troops deployed to the city was an FSB agent from Nalchik, Alexander Litvinenko, whose ad-hoc squad came under friendly fire from Grad rockets. Heavy losses (including friendly-fire incidents) triggered a collapse in morale among the Russian forces. Russian military analyst Pavel Felgenhauer reported that "based on information from observers and participants of the fighting, it can be concluded that Interior Ministry officers were on the verge of mutiny." It was reported that demoralized, cold and hungry Russian troops begged the locals for alcohol and cigarettes in exchange for ammunition.

A large group of relatives of the hostages gathered near security checkpoints 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) from the city and silently watched the bombardment. Russian authorities tried to minimize coverage of the crisis by blocking access to the scene with guard dogs, turning journalists away with warning shots and confiscating their equipment. The dogs injured several journalists (including an ABC cameraman and a correspondent for The Christian Science Monitor), and a reporter's car was fired on at a military checkpoint after being permitted to cross. Russian forces turned away relief workers, including representatives of Doctors Without Borders and the International Committee of the Red Cross. Reporters Without Borders protested Russian intimidation of the press in Pervomayskoye, its ban of medical assistance to civilians and its refusal to permit evacuation of the wounded.

(Spetznaz troops during the Siege of Kizlyar)

The Siege of Kizlyar resulted in 150 Russian, 200 Chechen and 900 hostages dead. The Russian government reacted hawkishly to the "liberation of Kizlyar"; Fyodorov initially said that "all the bandits have been destroyed, unless there are some still hiding underground", the operation was "planned and carried out correctly" and "is over with a minimum of losses to the hostages and our own people." One of top Russian officials said, "It is clear to everyone that it is pointless to talk to these people [Chechen jihadists]. They are not the kind of people you can negotiate with." U.S. Secretary of Defense William Perry affirmed solidarity with Fyodorov's government, saying that Russia was justified in using military force in response to hostage-taking. The operation triggered outrage in Dagestan and across Russia, especially in liberal circles. Prime Minister Grigory Yavlinsky criticized President Fyodorov and the Russian Military and said, "It is time to face the fact that we are in a real civil war now in Russia. This was not a hostage crisis. It is a hopeless war, even though it was started by us". Fyodorov's human-rights commissioner, resigned from all his posts in protest of the "cruel punitive action" and Boris Yeltsin drafted a letter calling on Fyodorov not to run in the upcoming presidential elections. In a January 19 Interfax poll, 75 percent of respondents in Moscow and Saint Petersburg thought that all the "power ministers" should resign.

The incident's handling was widely criticized by Russian and foreign journalists, humanitarian organizations and human-rights groups. Russian press accounts (including an account from Izvestia correspondent Valery Yakov, who witnessed the fighting from inside the city) described a chaotic, overmanned and bungled Russian operation in Kizlyar; Pavel Felgenhauer wrote that the armed services involved in the assault displayed a "fantastic lack of coordination." An opinion piece in The New York Times said, "All this bloodshed and confusion was dressed up in Moscow with Soviet-style propaganda, including false claims about minimal Russian losses and the elimination of enemy forces. The use of force against terrorism should be commensurate with the threat and employed in a way that limits the loss of life. Military action should be accompanied by full disclosure of information about the conflict and casualties. The murderous assault on Kizlyar did not meet any of those tests."

(Igor Ivanov - new conservative Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation)

The Ivanov doctrine was a Russian political doctrine formulated in the 1990s. It assumes that the national security of Russia relies on its superpower status and therefore Russia cannot allow the formation of a unipolar international order led by the United States. The doctrine takes its name from Igor Ivanov, who was appointed as the Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation by President Svyatoslav Fyodorov in 1996. Ivanov led the efforts to redirect the foreign policy of Russia away from the West by advocating the formation of a strategic trilateral alliance of Russia, China and India to create a counterbalance to the United States in Eurasia. The Ivanov doctrine revolved around five key ideas: Firstly, Russia is viewed as an indispensable actor who pursues an independent foreign policy; Secondly, Russia ought to pursue a multipolar world managed by a concert of major powers; Thirdly, Russia ought to pursue supremacy in the former Soviet sphere of influence and should pursue Eurasian integration; Fourthly, Russia ought to oppose NATO expansion; Fifthly, Russia should pursue a partnership with China. The doctrine led to the gestation of a Russia, India and China trilateral format, which would eventually become the BRICS.

Alone among the major combatants in World War II, Japan and Russia had yet to sign a peace treaty, fully normalizing their relations. The immediate cause of this anomalous situation was the inability of Tokyo and Moscow to agree on the ownership of the Kurile Islands, which the Soviet Union seized and annexed in the closing days of the war. The Soviets adopted the position maintained by their Russian successors—that they did this in agreement with their then ally, the United States, at the February 1945 Yalta Conference, the decisions of which Japan later accepted. In the Russian view, Japan consequently had no basis for disputing Russian sovereignty over the islands. The Japanese, however, argued that even though they ceded the Kuriles in the 1951 San Francisco Peace Treaty, these do not include the four southernmost islands—Etorofu, Kunashiri, Shikotan, and Habomai—which are an extension of nearby Hokkaido and hence part of Japan. Tokyo therefore insisted that these Northern Territories were illegally occupied by Russia and must be returned. The United States supported Japan’s position, but it did not begin to do so until the 1950s, when the intensification of the Cold War made it necessary to bolster Japanese support for the U.S.-Japan alliance.

The Northern Territories issue, as the Japanese called it, was not the only intractable territorial dispute in East Asia, nor was it a particularly explosive one in terms of its potential to spark conflict. The Japanese government had never been willing or able to contest the Russian occupation of the islands by force or the threat of force. It had instead kept the issue at the forefront of its bilateral dealings with Moscow, steadfastly maintaining its claim to the islands and insisting on their return as the sine qua non of a peace treaty and improved relations. A settlement held attractions for both sides. For the Japanese, it would write finis to what they see as the most humiliating legacy of World War II—foreign occupation of part of their national territory. In the view of many, a settlement would also facilitate their access to the rich natural resources of Siberia and the Russian Far East. For the Russians, improved relations with Japan offers the promise of attracting Japanese capital and technology to develop their eastern territories and integrate them with the dynamic East Asian economic region. Geopolitically, a Russo-Japan rapprochement would strengthen the hand of Moscow and Tokyo in dealing with a “rising China,” and support the Great Power ambitions of their political leaders and elites. While a deal on the Northern Territories might appear to be in the mutual interest of Russia and Japan, none has been forthcoming. During the Cold War, the issue was framed by Soviet-American rivalry in which Japan was a subordinate player. Stalin refused to discuss the status of the islands but Khrushchev, hoping to weaken the Japanese-American alliance, offered to return the two smallest ones (Shikotan and Habomai) after the conclusion of a peace treaty.

The Japanese were tempted, but Washington torpedoed the deal before it could be struck, and Khrushchev withdrew his offer in 1960. The one positive legacy of this episode was the reestablishment of diplomatic ties between Moscow and Tokyo in 1956. Until the late 1980s, however, Soviet-Japanese relations remained frozen. The Soviets dismissed Japan as an American client state and were contemptuous of its lack of military power and political clout in the international arena. Some Soviet observers were impressed by Japan’s economic growth and potential to contribute to Siberia’s development. But the Soviet leadership was indifferent to this potential and presented an inflexible face to Tokyo, denying that a territorial dispute even existed. Japan’s conservative leaders, for their part, reverted to the position that the return of all four islands was the precondition for a peace treaty and any improvement in relations. Soviet intransigence and belligerence were not entirely unwelcome to conservative Japanese leaders insofar as they provided a rationale for the American alliance and the buildup of the Self Defense Forces.

Soviet-Japanese relations became even frostier in the late 1970s and early 1980s as a result of Moscow’s displeasure with Japan’s endorsement of China’s stand against Soviet “hegemonism,” and Japanese alarm over the expansion of the Soviet Pacific fleet. Prime Minister Nakasone (1982-87) seized on the enhanced Soviet threat to strengthen military cooperation with the United States and assert Japan’s identity as a Great Power. The advent of Gorbachev marked a sea change in Soviet-Japanese relations. Intrigued by the possibility of using Japan to develop the stagnant and backward economy of the Soviet Far East, Gorbachev signaled flexibility by acknowledging the disputed status of the Northern Territories (or “South Kuriles” as the Soviets called them) and offering to negotiate a settlement. But while Tokyo welcomed this overture, it was suspicious of Gorbachev’s intentions and skeptical of his willingness to deliver substantive concessions. The Japanese consequently stuck to their Cold War position that a peace treaty and large scale Japanese economic assistance would depend on Soviet agreement to return the four disputed islands. This, however, was too much for Moscow hardliners to swallow and it fell to Gorbachev’s Russian successor, President Fyodorov, to try to cut a deal with Tokyo. Fyodorov was no less interested in attracting Japanese aid and investment, but Japan’s insistence on prior territorial concessions continued to pose a stumbling block inasmuch as such concessions were perceived by Russian nationalists as a humiliating surrender to foreign pressure and blandishments. Fyodorov, his hands tied by domestic resistance, could offer little more than a declaration of his intention to resolve the Northern Territories issue, and negotiations petered out in deadlock in the early 1990s. Stymied in his attempt to achieve a breakthrough with Japan, Fyodorov shifted his focus to developing a “strategic partnership” with China based in part on their common opposition to perceived U.S. “hegemonism.”

Last edited:

1. The Japanese and Russian governments have been discussing the issue of Kuril Islands for several months. Which diplomatic solution to this problem is the best?

A) Russia should give up all contested islands and sign the peace and commercial treaty with Japan;

B) Russia should give up only 2 smaller islands to Japan and sign commercial treaty;

C) Russia should not give up any contested islands.

2. A group of local activist have petitioned the Russian government claiming that Kaliningrad and Kaliningrad Oblast should be renamed into Nevskygrad and Nevskygrad Oblast to honor of the historical hero of Russia.

A) Agree to rename the city and the oblast;

B) Don't agree to the idea.

3. President Fyodorov have decided to appoint new prime minister after the upcoming presidential elections. Who is the most suitable candidate to this position?

A) Yevgeny Primakov (current Director of the FSB)

B) Anatoly Sobchak (Deputy Prime Minister for energy-fuel sector)

C) Boris Gromov (Interior Minister of Russia)

D) Gennady Zugyanov (Leader of the Communist Party - this decision would result in a coalition with the communists)

4. Please write down how should the Russian government deal with ongoing Islamist terrorist activities in the North Caucasus?

A) Russia should give up all contested islands and sign the peace and commercial treaty with Japan;

B) Russia should give up only 2 smaller islands to Japan and sign commercial treaty;

C) Russia should not give up any contested islands.

2. A group of local activist have petitioned the Russian government claiming that Kaliningrad and Kaliningrad Oblast should be renamed into Nevskygrad and Nevskygrad Oblast to honor of the historical hero of Russia.

A) Agree to rename the city and the oblast;

B) Don't agree to the idea.

3. President Fyodorov have decided to appoint new prime minister after the upcoming presidential elections. Who is the most suitable candidate to this position?

A) Yevgeny Primakov (current Director of the FSB)

B) Anatoly Sobchak (Deputy Prime Minister for energy-fuel sector)

C) Boris Gromov (Interior Minister of Russia)

D) Gennady Zugyanov (Leader of the Communist Party - this decision would result in a coalition with the communists)

4. Please write down how should the Russian government deal with ongoing Islamist terrorist activities in the North Caucasus?

1) A

2)A

3)B. Given the current foreign minister, appointing an anti-Western Primakov or Zyuganov looks like a strange decision that would have jeopardised half of all the decisions in the quest up to that point. And Gromov is somehow dreadful to trust, given the fact that in Russia the power structures are seizing power very quickly and quietly. In a normal situation I wouldn't risk appointing near oligarch Sobchak, but this is the best decision of the worst.

2)A

3)B. Given the current foreign minister, appointing an anti-Western Primakov or Zyuganov looks like a strange decision that would have jeopardised half of all the decisions in the quest up to that point. And Gromov is somehow dreadful to trust, given the fact that in Russia the power structures are seizing power very quickly and quietly. In a normal situation I wouldn't risk appointing near oligarch Sobchak, but this is the best decision of the worst.

Threadmarks

View all 149 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Federal budget Undermining American global financial domination (2010) New game GDP Ranking (2011) Chapter Thirty One: Nothing Lasts Forever (April - December 2010) Part I Chapter Thirty One: Nothing Lasts Forever (April - December 2010) Part II Map of the world (12/2010) Result of the vote (January 2011)

Share: