Chapter 2 - Part 3 - "How much does this provision not diminish the Royal Majesty in the eyes of the people" Testament Politique de Louis XVI, p. iv

Part 3 - "How much does this provision not diminish the Royal Majesty in the eyes of the people" Testament Politique de Louis XVI, p. iv

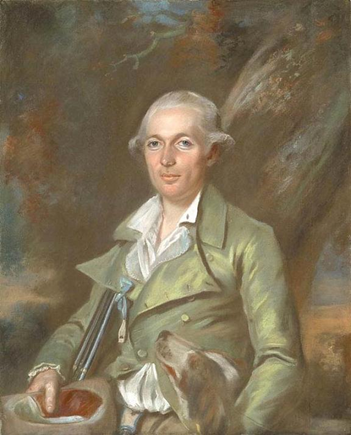

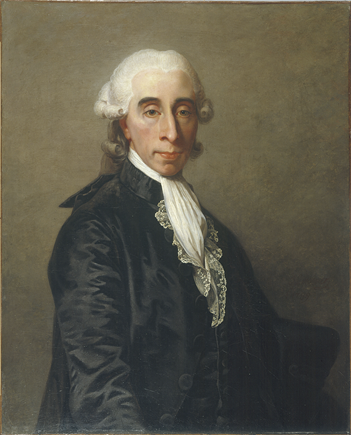

A later portrait of Claude-Antoine-Gabriel de Choiseul, Duke of Choiseul and Jean Sylvain Bailly

On the night of the 12th June 1791, the royal family performed their usual rituals, dismissed their servants for the night and went to bed. A short time later, timed to coincide with the departure of the Tuileries' many servants for their own beds, they rose again, donned, or were helped to don, their disguises and departed the palace one by one in the crowds. As a final flourish, von Fersen, perfectly imitating a Parisian coachman, picked up each member of the family in an ordinary hackney cab and ferried them to the prepared berline that was waiting on the outskirts. The execution was as brilliant as the plan and before any of the many suspicious eyes and minds of Paris, that had stopped the royal departure for Saint-Cloud only 2 months before, had realised, Louis XVI, Marie Antoinette, their children, his sister and their attendants had been spirited out of the city. It was an almost miraculous escape, free of delays or even much in the way of trouble. Louis XVI might perhaps have wondered if his previous procrastination had not been a pointless delay. It is more likely, though, that the royal family would have been doing nothing more than celebrating their success without a care in the world as they left behind the sleepy streets of Paris for the empty fields of the surrounding countryside.

Louis XVI had firmly believed that, once outside Paris, he would not only be free but that the French people would acclaim their loyalty and rally to him. This was a lasting effect of his only other journey outside Paris and the ring of royal palaces, his visit to Cherbourg in 1786. He had been cheered to high heaven then and he saw no reason why he shouldn't be on this occasion too, especially as Mirabeau had assured him only months before that the people of France were only waiting for his signal to oppose the National Assembly. [1] Indeed, it hadn't occurred to anyone in the royal coterie that they wouldn't be welcomed with anything other than loyalty. That particularly rude awakening would have to wait for at least one more night as, for now, everything continued to go smoothly. Indeed, as his family slept, Louis XVI himself treated it as a rare opportunity to inspect his kingdom, counting every mile posts along the roadsides, naming each village they passed through and keeping track of their progress with a time-table that had been prepared by von Fersen and his fellow conspirators.

As night turned to day, the carriage was joined by a second, carrying the children's nurses, and kept moving whilst France woke up around them. The royal family were blissfully unaware of the chaos engulfing Paris, though Marie Antoinette did jokingly remark on how shocked 'Mr Lafayette' must be [2], and so were the peasants waking up to tend the fields. As far as any of them knew, a strange cavalcade, probably belonging to a noble family to judge from its ostentation, was travelling on an every day journey. It was hardly an unusual sight. This was another stroke of luck, one of the bodyguards later recalled that they had nearly purchased livery in the colours of hated local noble before choosing better made, but more expensive, outfits. [3] Paris, meanwhile, was the opposite of this country idyll and was in an emergency. No-one had realised anything was amiss until the royal servants drew back the bed curtains in the morning to find that their master and mistress were absent. From there, the news had spread like wild fire. The palace staff and guards had combed the buildings and grounds in the vain hope that the royal family had somehow just gone for an early morning stroll. But it was all to no avail and news that the king had either betrayed the revolution or been kidnapped by traitors and foreign agents quickly filled the streets of Paris.

As soon as they heard what had happened, less than an hour after those servants had first drawn back the curtains, Lafayette and Bailly both rushed to the scene of the crisis. Arriving at the Tuileries with a hastily assembled body of National Guards, their party was booed and jeered by portions of the crowd that was massing at the palace gates. The two men, and the National Guard, were already being blamed by some of the Parisian mob for either incompetence or complicity in the King's departure. The crowds had no idea, of course, of Lafayette and Bailly's very real shock and feeling of betrayal, both men had been due to meet Louis XVI in the palace that very day, and it probably wouldn't have mattered even if they had known. In a France that still believed in Louis XVI and his many promises to them, the idea that he had abandoned Paris by his own free will was simply inconceivable.

It was with this in mind that Lafayette and Bailly joined the search of Tuileries themselves, but they too found no trace of the royal family or any indication of a reason for their departure. As a result they jointly issued a proclamation declaring that the royal family had been kidnapped by unknown agents and stolen away as either hostages or future puppets for the enemies of France. A very similar proclamation was issued shortly afterwards by the National Assembly, which had met almost spontaneously as the news reached its members and they could only think to gravitate to their meeting hall. The Assembly also declared a national emergency by unanimous vote and dispatched messengers in all directions to join the many that had already been sent out by Lafayette, by Bailly, by the Jacobin Club and other political clubs and by numerous private individuals. The first messengers had borne simple message 'The King has left Paris'. Their later, more official, counterparts were now told to say that the King had been kidnapped instead. This convenient fiction, which at least had nothing to disprove it as yet, had become the official line already and would remain so. [4]The alternative was too alarming about for all but a select number of radicals, primarily centred around the Cordeliers Club.

With messengers in pursuit, the royal cavalcade trundled onwards at a stately pace, occasionally stopping to change horses. By noon, Louis XVI was convinced enough in his own safety to climb down from the carriage at these stops to talk with the locals. [5] This had been one of his favourite past-times, even at Versailles, and demonstrated his sincere interest in the concerns and ideas of his people, even if he was seemingly unable to grasp how to actually help them. On this occasion, few knew who he was, though many would later claim to have recognised him. These conversations nonetheless added to the almost holiday atmosphere as the royal family made its way to their final destination at Montmedy. [6] The only dampener was that von Fersen had left the party in the morning to ride off to the Austrian Netherlands, his job well done. In his stead, the royal family would soon be joined by the first of Bouillé's German and Swiss cavalrymen commanded by Claude-Antoine-Gabriel de Choiseul, Duke of Choiseul, at Somme-Vesle. Then the royal procession would be complete and it would only be a short and well-guard route to Montmedy.

A later portrait of Claude-Antoine-Gabriel de Choiseul, Duke of Choiseul and Jean Sylvain Bailly

On the night of the 12th June 1791, the royal family performed their usual rituals, dismissed their servants for the night and went to bed. A short time later, timed to coincide with the departure of the Tuileries' many servants for their own beds, they rose again, donned, or were helped to don, their disguises and departed the palace one by one in the crowds. As a final flourish, von Fersen, perfectly imitating a Parisian coachman, picked up each member of the family in an ordinary hackney cab and ferried them to the prepared berline that was waiting on the outskirts. The execution was as brilliant as the plan and before any of the many suspicious eyes and minds of Paris, that had stopped the royal departure for Saint-Cloud only 2 months before, had realised, Louis XVI, Marie Antoinette, their children, his sister and their attendants had been spirited out of the city. It was an almost miraculous escape, free of delays or even much in the way of trouble. Louis XVI might perhaps have wondered if his previous procrastination had not been a pointless delay. It is more likely, though, that the royal family would have been doing nothing more than celebrating their success without a care in the world as they left behind the sleepy streets of Paris for the empty fields of the surrounding countryside.

Louis XVI had firmly believed that, once outside Paris, he would not only be free but that the French people would acclaim their loyalty and rally to him. This was a lasting effect of his only other journey outside Paris and the ring of royal palaces, his visit to Cherbourg in 1786. He had been cheered to high heaven then and he saw no reason why he shouldn't be on this occasion too, especially as Mirabeau had assured him only months before that the people of France were only waiting for his signal to oppose the National Assembly. [1] Indeed, it hadn't occurred to anyone in the royal coterie that they wouldn't be welcomed with anything other than loyalty. That particularly rude awakening would have to wait for at least one more night as, for now, everything continued to go smoothly. Indeed, as his family slept, Louis XVI himself treated it as a rare opportunity to inspect his kingdom, counting every mile posts along the roadsides, naming each village they passed through and keeping track of their progress with a time-table that had been prepared by von Fersen and his fellow conspirators.

As night turned to day, the carriage was joined by a second, carrying the children's nurses, and kept moving whilst France woke up around them. The royal family were blissfully unaware of the chaos engulfing Paris, though Marie Antoinette did jokingly remark on how shocked 'Mr Lafayette' must be [2], and so were the peasants waking up to tend the fields. As far as any of them knew, a strange cavalcade, probably belonging to a noble family to judge from its ostentation, was travelling on an every day journey. It was hardly an unusual sight. This was another stroke of luck, one of the bodyguards later recalled that they had nearly purchased livery in the colours of hated local noble before choosing better made, but more expensive, outfits. [3] Paris, meanwhile, was the opposite of this country idyll and was in an emergency. No-one had realised anything was amiss until the royal servants drew back the bed curtains in the morning to find that their master and mistress were absent. From there, the news had spread like wild fire. The palace staff and guards had combed the buildings and grounds in the vain hope that the royal family had somehow just gone for an early morning stroll. But it was all to no avail and news that the king had either betrayed the revolution or been kidnapped by traitors and foreign agents quickly filled the streets of Paris.

As soon as they heard what had happened, less than an hour after those servants had first drawn back the curtains, Lafayette and Bailly both rushed to the scene of the crisis. Arriving at the Tuileries with a hastily assembled body of National Guards, their party was booed and jeered by portions of the crowd that was massing at the palace gates. The two men, and the National Guard, were already being blamed by some of the Parisian mob for either incompetence or complicity in the King's departure. The crowds had no idea, of course, of Lafayette and Bailly's very real shock and feeling of betrayal, both men had been due to meet Louis XVI in the palace that very day, and it probably wouldn't have mattered even if they had known. In a France that still believed in Louis XVI and his many promises to them, the idea that he had abandoned Paris by his own free will was simply inconceivable.

It was with this in mind that Lafayette and Bailly joined the search of Tuileries themselves, but they too found no trace of the royal family or any indication of a reason for their departure. As a result they jointly issued a proclamation declaring that the royal family had been kidnapped by unknown agents and stolen away as either hostages or future puppets for the enemies of France. A very similar proclamation was issued shortly afterwards by the National Assembly, which had met almost spontaneously as the news reached its members and they could only think to gravitate to their meeting hall. The Assembly also declared a national emergency by unanimous vote and dispatched messengers in all directions to join the many that had already been sent out by Lafayette, by Bailly, by the Jacobin Club and other political clubs and by numerous private individuals. The first messengers had borne simple message 'The King has left Paris'. Their later, more official, counterparts were now told to say that the King had been kidnapped instead. This convenient fiction, which at least had nothing to disprove it as yet, had become the official line already and would remain so. [4]The alternative was too alarming about for all but a select number of radicals, primarily centred around the Cordeliers Club.

With messengers in pursuit, the royal cavalcade trundled onwards at a stately pace, occasionally stopping to change horses. By noon, Louis XVI was convinced enough in his own safety to climb down from the carriage at these stops to talk with the locals. [5] This had been one of his favourite past-times, even at Versailles, and demonstrated his sincere interest in the concerns and ideas of his people, even if he was seemingly unable to grasp how to actually help them. On this occasion, few knew who he was, though many would later claim to have recognised him. These conversations nonetheless added to the almost holiday atmosphere as the royal family made its way to their final destination at Montmedy. [6] The only dampener was that von Fersen had left the party in the morning to ride off to the Austrian Netherlands, his job well done. In his stead, the royal family would soon be joined by the first of Bouillé's German and Swiss cavalrymen commanded by Claude-Antoine-Gabriel de Choiseul, Duke of Choiseul, at Somme-Vesle. Then the royal procession would be complete and it would only be a short and well-guard route to Montmedy.

[1] This was part of Mirabeau's plan to persuade local governments across France to write petitions against the National Assembly. Mirabeau's death prevented it ever being tested.

[2] She reportedly made the same joke or very similar one during IOTL's Flight to Varennes as well.

[3] A minor change, but it may have helped the royal family get caught IOTL.

[4] Louis XVI is persuaded not to leave before his Declaration to the French People is completed, so he takes it with him ITTL.

[5] He did this IOTL as well.

[6] Contrary to popular belief, they had no intention of fleeing the country.

Last edited: