The Somali loss in the 1963-64 border war had not snuffed out the dream of

Soomaaliweyn, a Greater Somalia uniting the Horn of Africa in a single state. Ogaden Somali notables that had fled to Somalia after the suppression of the

Nasrallah insurgency had consistently lobbied the parliamentary and revolutionary governments for continued support. These groups were particularly influential on Siad Barre, due to belonging to the same clan family as him, the Darod. Whilst the first few post-revolutionary years had the

Guulwade focus on internal considerations, particularly the undermining of potential opposition forces, by the mid-1970s he was making preparations for a rematch with the Emperor[195]. Between 1974 and 1977, the Somali Democratic Republic would receive over $300 million of military aid from the USSR and its allies. The Somali National Army (

Ciidanka Xooga Dalka Soomaaliyeed, C.X.D.S) was no longer the anemic militia force that had stared down the Imperial Army across the border a decade earlier. Equipped with modern weapons and boasting one of the numerically largest armies in sub-Saharan Africa, it had been shaped into a formidable fighting force. Unlike most armies of the continent, it wasn't merely designed to suppress dissent either; most of its leadership were graduates of the Frunze Military Academy in Moscow, and the presence of Soviet advisors kept it doctrinally modern. The air force had also been modernised, with pilots sent abroad to the United Kingdom, Italy, the USSR and the United States to improve their skill. The Somalis also purchased four Ilyushin Il-28 bombers and 29 MiG-21s; a further fifty MiG-17s were donated by the Soviets. Across the border, two resistance groups sponsored by Mogadishu were making preparations: the Western Somali Liberation Front (

Jabhadda Xoreynta Somali Galbeed, JXSG) had been slowly recruiting since the late 1960s and was formed around a core group of veteran Nasrallah fighters. 1976 saw another organisation, the Somali Abo Liberation Front (SALF) announce its formation. SALF was an Oromo liberation movement which sought independence from Ethiopia and union with Somalia, despite the distinct ethnic identity of the Oromo. Both groups rapidly increased their recruitment and propaganda activities in 1975 and 1976, something that didn't go unnoticed by Addis Ababa.

On June 1977, JXSG guerrillas cut the vital Ethiopian railroad link between Addis Ababa and Djibouti. A month later, on July 12th, a full-scale invasion began, with the vanguard of the invasion disguised as Ogaden Somali guerrillas. This ruse fooled nobody, for where could the JXSG guerrillas, comprised of local goat and camel herders, have acquired modern fighter jets and main battle tanks? The C.X.D.S made rapid advances into the Ogaden region, winning several spectacular battles against the Imperial Ethiopian Army (IEA). Whilst the army of the

negusa nagast was one of the only ones in Africa who could numerically match (and in fact, exceeded) the C.X.D.S, it was massively outmatched in terms of artillery and armoured vehicles and, even more importantly, was structured more towards the suppression of internal rebellions such as those of a decade earlier, or the ongoing rebellion in Eritrea, unlike the C.X.D.S, which was designed to defeat the Ethiopians in open battle. The JXSG guerrillas provided a further tactical advantage for the Somalis, providing up to date reconnaissance and could assist in the governance of occupied areas. In the 1960s the Ethiopians had the upper hand against the Somalis due to a massive numerical and equipment advantage. Now, they were being crushed by an enemy force that was a completely different beast. The IEA was unable to gain its footing as Somali tanks encircled them and stationary positions were hammered with heavy artillery bombardment. The only area where the Ethiopians were having some success was in the air. Despite having a smaller air force than the Somalis, the Imperial Ethiopian Air Force (IEAF) were an elite group, trained extensively by US advisors. With the only possible exception of South Africa, the IEAF fighter pilots were the most well-trained combat pilots in sub-Saharan Africa. They were able to give the Somalian air force a bloody nose, but were unable to establish air superiority. Whilst the skies were heavily contested, on the ground the C.X.D.S meet little initial resistance. Within a month, 70% of the huge Ogaden region was occupied by the Somali National Army. There were some early setbacks, most notably in the north, where the Somali National Army attempted a surprise attack on Dire Dawa (Somali:

Diridhaba) on July 16th. The city was a key strategic target for the C.X.D.S. Whilst it had historic importance for the Somalis (it's name translates to "where Dir [ancestor of the Dir Somali clan] struck his spear into the ground"), the ethnically mixed Oromo-Somali city was in a key position on the railroad between Djibouti and Addis Ababa. Taking Dire Dawa would isolate the Ethiopians from outside support and resupply. The city was also home to the second-largest airbase in Ethiopia. Without it, the Ethiopians would lose the ability to contest the air in the whole northern half of the front. Despite being outnumbered and outgunned, the Ethiopian garrison was able to valiantly hold out until the arrivement of reinforcements from Harar. In part this was made possible by the efforts of the combat pilots in the skies above, who managed to defeat their Somali air force opponents and even mount a counter-strike, bombing the Somali airbase at Hargeisa, destroying a number of MiGs on the ground. The IEAF now had a slight numerical advantage to complement their qualitative edge. Without this victory in the air, the Ethiopians would have been unable to repulse the encroachment of the Somali T-55 tanks, their army's antiquated recoilless rifles harmless to the Soviet-made main battle tanks. Despite a brief scare when the Somali tanks managed to temporarily take the airport, a vigorous (and desperate) Ethiopian counterattack had managed to expel the Somalis.

Dire Dawa one year after the end of the war, note the bullet holes on the building to the right.

On the diplomatic front, contentious debate raged in the chambers of the UN General Assembly and the Security Council. African states were divided between support for Addis Ababa and Mogadishu. Socialist African states celebrated the Somali Democratic Republic for committing to a "national liberation struggle" whereas the Western-aligned states rejected the claim that Haile Selassie of all people, was an "imperialist oppressor". In the Security Council, vetoes were traded, with the US, France and United Kingdom proposing an immediate ceasefire and total withdrawal of Somalian troops, whereas China and the USSR proposed a referendum for independence for the Ogaden region. Knowing that this would likely result in the secession of the region from Ethiopia, the Western powers rejected this proposal. Both Somalia and Ethiopia aggressively lobbied for military aid; the Soviets agreed to sell Mogadishu more MiGs, whilst the Chinese offered small arms and ammunition shipments to Somalia free of charge. The Americans offered only token support; East Africa was not a key area of strategic interest for the Wallace administration. The French were more forthcoming. Believing that a Somali victory in the Ogaden War would turn their attention next towards Djibouti, Paris offered artillery pieces and shells, small arms and ammunition, and ten AMX-30 main battle tanks. These would take time to arrive, however, and in the meantime the Somali National Army was making gains.

Undeterred by the initial rebuke at Dire Dawa, the C.X.D.S regrouped and assaulted the town of Jijiga. A large tank battle took place outside the city, where 124 Somali T-55s were met by 108 Ethiopian tanks, mostly M47 Patton medium tanks and M41 Walker Bulldog light tanks. Not only were the Ethiopian tanks outnumbered, but the more modern T-55s were superior in virtually every category. The result was a crushing defeat for the Ethiopian armoured force; nearly half of their total number was destroyed entirely, with the remainder forced to withdraw and leave Jijiga to its fate. Early in the battle, a Somali artillery barrage had managed to disable the radar array atop Mount Karamara, limiting the ability of the IEAF to provide close air support. By September 12th, Jijiga had fallen into Somali hands. A day later, the Somali National Army secured the strategic Marda Pass on Mount Karamara. The path was now open to Harar, the city which the Somali Youth League had claimed should be the capital of a united

Soomaaliweyn. Meanwhile, in the south, the Somalis were advancing to the edge of the Ethiopian plateau, breaking into the Oromo region of Bale province. Here the SALF was having some success with rallying local Oromo to support the offensive. Whilst not as universally-supported as the JXSG guerrillas were in the Ogaden, SALF had nevertheless been able to gain recruits from nationalist Oromo who hoped to see their Somali allies establish an independent Oromia [196]. Driving into the region with support from the SALF, who harried Ethiopian militia forces in the area, the C.X.D.S was able to dislodge the Ethiopians on this part of the front too, seizing the provincial capital of Goba. In order to further cement their control over the region, the Somalis established from the leadership of SALF the "Provisional Government of Liberated Oromia" (Oromo:

Mootummaa Yeroo Oromiyaa Bilisoomte). In order to shorten the front, the C.X.D.S also pushed into the southeastern part of Sidamo province, taking Filtu and Kusa, but halted their advance in that sector.

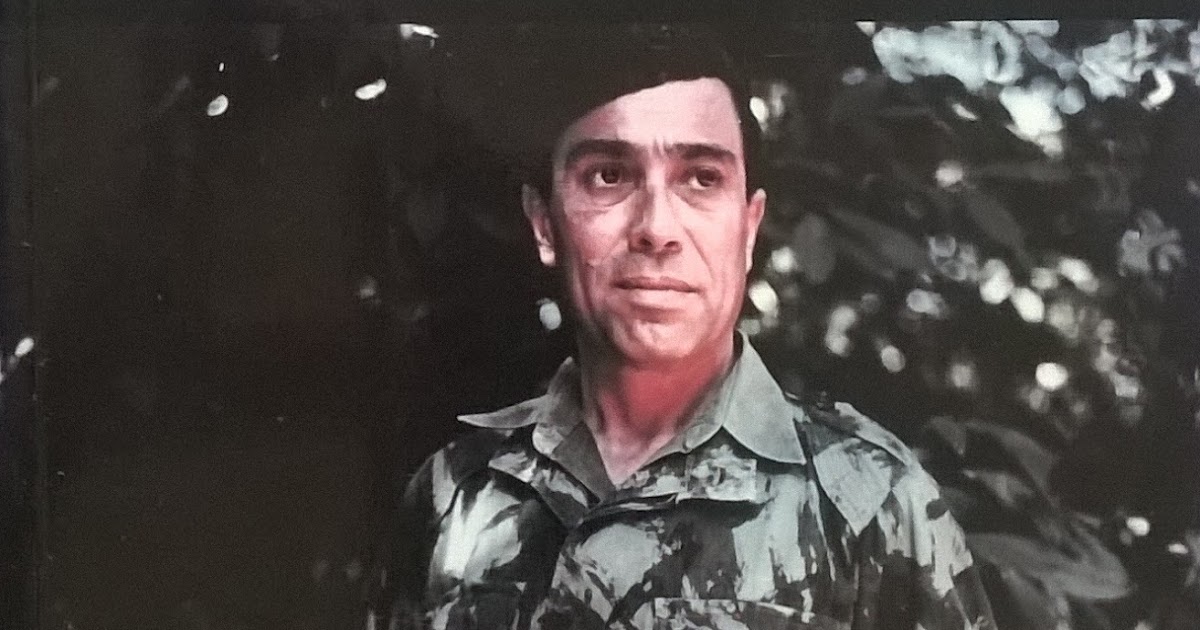

Female fighters of the Western Somali Liberation Front

Back in the north, the Somali National Army regrouped and reorganised, having been stretched by its rapid advances. Turning its sights to the city of Harar. A vigorous Ethiopian defense eventually crumbled under sustained Somalian attacks, although it took seven weeks to breach the defensive lines around the town. Harar would finally fall in December, after four months of sustained attack by the Somalian forces. As they marched into the town, the local Hararis sung songs in celebration, for they had suffered brutally under the imperial regime. Somali forces were informed by the locals of a mass grave on the outskirts of the city; it was filled with the bodies of locals who had attempted a spontaneous uprising against the Ethiopian troops stationed in the city. In response, the Somalis and their local Harari allies slaughtered en masse the captured Ethiopian soldiers. As the war was getting more desperate and brutal, war crimes on both sides were starting to pile up. Even in the occupied regions, notably in Bale Province, local SALF and JXSG guerrillas were committing massacres against towns of settlers from other parts of Ethiopia. Most grisly were the scenes at the Amhara settlements: rape and mutilation were commonplace, along with the desecration of churches. No abuse of the imperial regime had been forgotten, and local militants were ensuring that every slight would be returned in kind. This was the way of war in East Africa. In the time that the Somalis had needed to take Harer, the Ethiopians had raised a number of militia units and began to dig in at Dire Dawa and the approaches to the central Ethiopian highlands. February 6th 1978 saw a Somali offensive whose objective was to finally seize Dire Dawa, the last major strategic target outside of Somalian occupation. Whilst the Ethiopians were now dug in, the Somali forces had a secret weapon that their command believed would ensure victory in the Second Battle of Dire Dawa: a battery of Soviet surface-to-air missiles[197]. The 2K11 "Krug" and 2K12 "Kub" tracked missile launchers were expected to ensure air supremacy, allowing the Somali air force to bombard the Ethiopian defensive positions outside the town and, when combined with a massive artillery bombardment and an armoured assault, would prove decisive. They were ultimately correct, even though the fighting still took longer than anticipated, with the town finally falling on April 18th. Siad Barre sent out offers of an armistice to Haile Selassie, which would force him to relinquish control over Oromia, Haraghe and Ogaden, leaving only a rump Ethiopia. Unsurprisingly the offer was rejected. It looked like the Somalis would be forced to march on Addis Ababa, leaving the Emperor with no choice in the matter. After regrouping again, the Somalis launched a powerful push along a single axis of attack: pushing along the railway line from Dire Dawa to Nazret, just outside Addis Ababa. Despite the long frontline, Siad Barre's generals advised against a wide advance. The local populations of the highlands were largely hostile to the Somalis and would tie up massive numbers of troops with guerrilla warfare, and the terrain was difficult to advance through. There was a reason Ethiopia's period under European rule lasted less than a lifetime; the country was a natural fortress. Instead, the Somalis reasoned, a single column of advance could force through to Addis Ababa, albeit with fairly significant losses. It was hoped though that Somali artillery superiority, and the ability of the Soviet-supplied SAMs to limit the efficacy of Ethiopian airstrikes, would prove enough to prevent ambush along the route.

The march southwest for the Somalis would be grueling: the Imperial Ethiopian Army maintained strongpoints along the roads, making the invaders pay in blood for every kilometre taken. Dragon's teeth emplacements, barbed wire obstacles and minefields slowed the Somalian advance to a crawl. Somalian combat engineers trying to clear minefields were shot at by concealed snipers. This type of warfare couldn't look more different from the triumphant, rapid advance of the C.X.D.S in the first month of the war. Nevertheless, slowly but surely the Somalis continued their advance. The distance specks in the sky, the Ethiopian jets, rarely approached too close in fear of the state-of-the-art Soviet SAMs. Certainly not close enough to see that they were actually manned by Soviet "advisors". The Somalian artillery also proved its worth, softening enemy defensive emplacements and providing cover for Somali infantry by cratering the ground. In a way it also allowed for a form of

ad hoc, if not entirely reliable, mineclearing. It wasn't until September 1978 that the Somali National Army was approaching the outskirts of Nazret. It was at this point that the Somalis got word that Haile Selassie, their hated foe, had passed away in his sleep at the age of 86 [198]. Whilst the Ethiopian government had tried to keep it quiet, the truth nevertheless spread quickly through Addis Ababa, with the locals publicly mourning the death of their beloved Emperor. Upon hearing of the news, Siad Barre celebrated. One thing that would be sure to ensue would be palace intrigues; the nobility of Ethiopia would surely backstab each other to gain influence over Haile Selassie's successor. Selassie would be succeeded by his thirty-five year-old grandson Zera Yacob Amha Selassie. With Haile Selassie dead and a political crisis about to brew, the Ethiopian Army tried one last gambit against the approaching Somalian forces: spearheaded by the French-supplied AMX-30 main battle tanks, the Ethiopians mounted a desperate armour and infantry offensive against the Somalis outside of Nazret. Forced to attack along a narrow front due to the terrain, it was a slaughter. Most of the tanks were disabled in the first few hours as a result of artillery barrages, whilst the poorly-trained but numerous Ethiopian militias charged directly into Somalian gunfire. Some of them managed to get close enough to the Somali lines, and casualties were heavy on both sides as the Ethiopians desperately sought to defend their capital against the invader. Overhead, the Ethiopian air force massed all its forces in a single desperate assault on the Somali column. Practically ignoring the enemy MiGs, the Ethiopians beelined it for the Somali tanks, managing to destroy many of them with air-to-ground missile fire before being shot down by SAMs or Somali warplanes. The explosions of jetfuel that climbed into the sky as the frontline infantrymen engaging in close quarters combat gave the scene an apocalyptic tilt; it was if the whole world had finally gone mad. Shrieks and warcries climbed bounced off the mountainous hills, drowned out by the sounds of modern technological warfare. Was it here that the warrior traditions of East Africa would consume themselves, finally buried under the tracks of tanks and a rain of missiles? The air overhead was empty of Ethiopian planes just as the Somali lines began to break under the Ethiopian onslaught. Then suddenly, almost imperceptibly amongst the din of battle, the shells began to whistle down, and rockets with them. Somali and Ethiopian troops alike where being torn asunder by the most concentrated air and artillery bombardment yet. And it was at this moment that some of the Somalian troops, the ones whose magazines hadn't entirely emptied and who weren't engaged in hand-to-hand, eye-to-eye combat with the hated Ethiopian enemy, came to realise a shocking truth; that the air and artillery bombardment that was killing their comrades was from their own side. They would be remembered as selfless martyrs, but they wouldn't be given a choice.

Siad Barre had personally ordered the counter-bombardment from a field command post at Dire Dawa. He expected the Ethiopians to desperately try to attack in force at least once before his troops arrived at their capital. In order to prevent the breaking of the line, drastic action had been necessary. He had hesistated little. The Somali National Army had more infantry in reserve, and the front rows were packed with Isaaqs anyway. For all of his talk of pan-Somalism, Siad Barre hated the Isaaqs. He was only a boy of ten years old when he saw his father murdered in front of his eyes by Isaaq clansmen. In his view, it was only right that they bleed more than most to unite the

Qeexitaanada, the homeland. Anyway, the bombardment had worked. The Ethiopian assault was halted. The enemy was spent. They sued for peace and negotiations began. Despite their position, they had refused total independence for the Oromo lands. The Jackson highway went south through the Rift Valley Republic and into the Great Lakes region, and they refused to cede it. They did relinquish the entirety of Bale Province, including the Oromo-inhabited areas, as well as the small southeast parts of Sidamo occupied by Somalia. Almost the whole of the Harerghe region was annexed by Somalia, excluding the small Afar-inhabited area around Gewane. Dire Dawa, Harar, and Jijiga would of course become Somalian territory. Of course the Ogaden would be taken in its entirety too. This war had been long and hard, but in the end, it was a total victory.

Poster representing Greater Somalia (all irredentist claims)

===

[195] ITTL, the Derg don't topple Haile Selassie's regime. Whilst still fairly feudal and majorly-underdeveloping certain areas, the economic situation is better than OTL, particularly in the Amhara-inhabited areas, largely due to a greater degree of investment in Ethiopia by the Jackson administration. This prevents the Derg from getting enough support to take power. More will be revealed in detail in a future update.

[196] IOTL the SALF was unable to garner much support due to a lack of credibility amongst the Oromo. Also, the Oromo were actually overrepresented in the Derg regime, leading most Oromo to side with Addis Ababa. ITTL, with an imperial Ethiopian government still in power, the Oromo are more enthusiastic about supporting the Somali advance.

[197] IOTL, with the Soviets aligning themselves with the Derg, the Somalis were unable to get resupplied, making their supply lines stretch earlier and eliminating their ability to get new equipment. Furthermore there is obviously no Cuban-Soviet intervention ITTL; where Cuba is not part of the Soviet bloc, and the Soviets aren't allied with a still-Imperial Ethiopia.

[198] IOTL he was murdered by the Derg in 1975.

--

Edit note: I had to change the usual format for the C.X.D.S acronym, as having X and D together would be converted by the site into a laughing emoji. Does anyone know how to disable this?

Edit: You'll also note that my world map didn't show the territorial changes from this conflict. That was an oversight on my part (sorry)